Online School’s Most Difficult Classes

Teachers and students of hands-on classes speak out about their experiences on Zoom

February 8, 2022

Coming out of online school, we all have our fair share of stories about disastrous online mishaps, endless zoom calls from the early morning, and curriculums that were poorly adapted to the new format. But perhaps underappreciated during this sometimes painful era of online school were the school’s hands-on classes. These classes were the most difficult to adapt to a remote learning format, and the ones with surprising amounts of success.

Classes that need direct experience to learn were, predictably, tough for teachers to teach online. Diana Dillard, the culinary arts teacher, had a hard time adapting the way she taught her class to the new format.

“Everything had to change,” she said. “My first initial reaction, even though I’m a very positive person, was that I can’t do it.” For Dillard, it was a massive learning curve— she needed to find all new resources that would work for teaching kids online, and needed to utilize every bit of creativity and resourcefulness she had in order to make it work.

“I had a lot of academic freedom, and [the district] trusted me to implement what I needed to,” Dillard said. “But there‘s a downside to that. You don’t have anyone to bounce ideas off of and get ideas from.”

She wasn’t the only one who had trouble with these changes, either. Wesley Proudlove teaches both robotics and auto tech, both classes which require a lot of observation and technical hands-on experience. “It’s a hands-on class, so not having kids here to do things in the shop is a concern,” Proudlove said.

With the issues of online school, it seemed as though the challenges were just too many to count, but online resources and restructuring of old material made it a little bit easier. “I had a past student of mine get some of my videos we used during class, and he put them in a format we could use on Zoom,” said Proudlove. “We kind of broke the code of the program so we could share it on Zoom.”

Despite the challenges the teachers encountered, these experience-based classes were certainly not neglected. The district splurged on their budgets, providing them with just about everything they might need for success online.

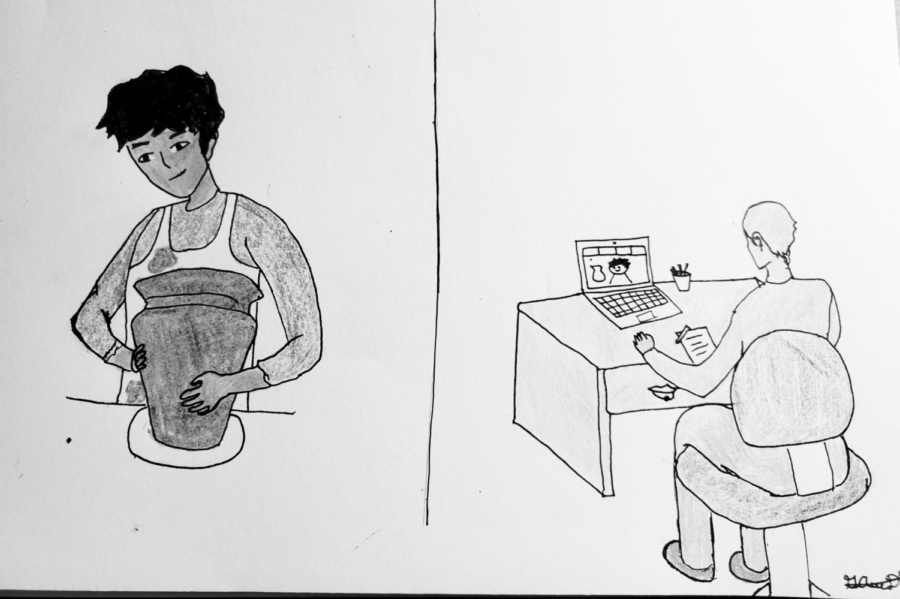

“We broke the bank,” Proudlove said. “We spent literally thousands per kid, and if [they] took robotics and auto tech, that’s a couple of thousands of dollars of equipment they got to take home.” But even with this extra monetary support, there were still hurdles to jump, especially in getting students the tools they needed. Michael Zadra, the ceramics teacher, had difficulties with getting kids the essential elements of their curriculum.

“When we first went remote, I wasn’t able to distribute clay to the students because there were concerns about transferring COVID-19. Students were no longer able to build projects,” Zadra said. It wasn’t until the start of the next school year in ceramics that students were able to take home essential materials.

Eventually, however, the classes got what they needed, and students were provided with plenty of resources. In culinary arts, they were able to send home tools for their students to use in their own kitchens. “On Wednesdays, [students] would pick up lab products here at Shorewood in the garden, and then they would take those home and do the lesson on Zoom,” Dillard said. Sometimes, they were even able to provide opportunities at home for students that perhaps they wouldn’t have been able to give them otherwise. In Proudlove’s robotics class, the exceptionally large budget paired with the virtual setting to give kids more interesting learning opportunities. “We sent home $1,500 robots, sometimes $2,000 robots, to each kid [for them] to work on at home,” Proudlove said.

Nevertheless, many teachers of hands-on classes remain adamant that the quality of learning in their classes took a hit online. “There were some good tools that came out of [virtual school], but it was absolutely inferior to being in-person,” Dillard said. Even with the proper funding and tools to succeed, it was difficult to live up to the community and hands-on learning that kids got in person, inside the classroom.

Among the teachers, the opinion that online learning can’t compare to the quality of in-person instruction is prevalent. But some students feel differently. Emma Russell and Libby Crowe are students in culinary arts who experienced the class both online and in-person, and they’ve had their fair share of quarantine woes. In early 2020, when schools first shut down, Russell was part of a group of students who had prepared a full-course meal for the culinary arts chef dinner event, which was cut short right before it was about to start by the stay-at-home mandate. “[In person], you really look forward to all the events, because we do chef dinners, lunches, and catering,” Russell said. “During quarantine, it was slow, and you didn’t really get to talk to people.”

But both Russell and Crowe agree that culinary arts was still a great class to take over quarantine, despite the setbacks of online learning. “I would say it was almost a different class,” said Crowe, comparing her experience in online culinary arts to in-person class. “We still learned a massive amount.” Although they weren’t able to learn cooperation skills and experience the culinary arts community built, online culinary arts still had a lot of strengths, and a lot to teach them. “Since we were doing everything [in the kitchen] by ourselves, [online class] was a lot different,” Crowe added. “It’s definitely prepared us well, and we’ve learned how to rely on ourselves and be independent.”

These benefits may not come as a suprise. Some of the teachers also observed that some students benefited from the online framework. Last year, Proudlove had a student who was formerly very reserved and quiet during class, who found his voice in online learning. “[This student] was super quiet before the pandemic. I thought he would fall apart during the pandemic, but every day he talked to me on Zoom, when before he barely said a sentence to me,” Proudlove said. “Now he’s going on to community college to work in robotics, which is crazy. He never would have done it before.” Quarantine almost served as a great equalizer in some respects for the hands-on classes of Shorewood. In other respects, it was a massive setback.

But in the end, despite the mixed bag of experiences and responses to the challenges online schooling posed, we got through it. In the aftermath of such a strange experience, teachers’ perspectives on teaching have changed, and so has their students’ regard for all of the different facets to a hands-on learning experience. “At Shorecrest, they just didn’t offer ceramics at all during covid,” said Zadra. “I’m grateful that we were able to solve problems and still offer the class. It wasn’t perfect, but it was still beneficial for students who took it.”