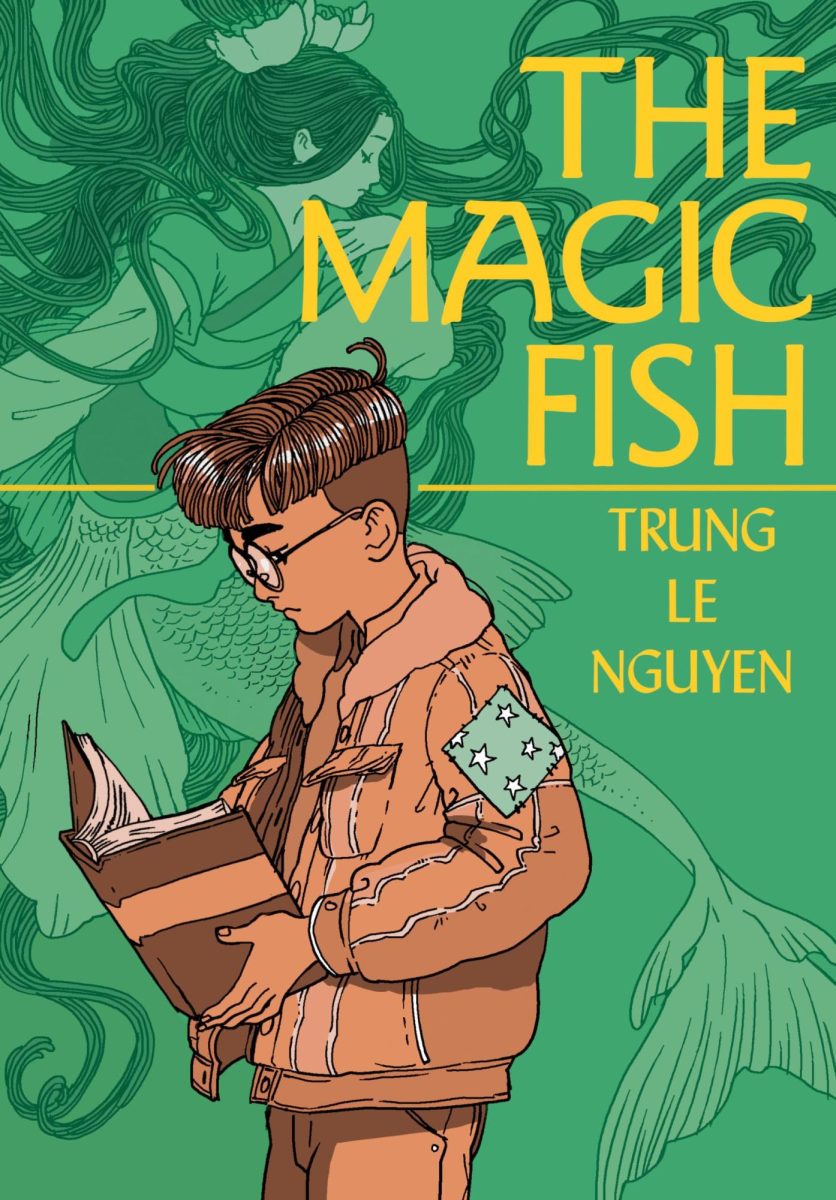

When I finished reading this book, I had no words for it. And that is probably the most accurate, possibly the only way to describe “The Magic Fish” (2020), where stories mean something far greater than just words.

The book follows Tiến and his Vietnamese mother Helen, reading fairy tale books to each other as they’ve been since he was very young. While fairy tales started as Helen’s way to learn English, they soon became very significant memories connecting her with her son and the central element throughout the plot. From “Cinderella” to “The Little Mermaid,” the story introduces fairy tales that have been told for many centuries, but with a creative perspective and jarring twists. I loved how the author illustrated the story so that these fairy tales paralleled the real struggles that Helen and Tiến were experiencing in their lives: the distance Helen felt between her son from growing up in two different cultures and Tiến’s fear of not being loved anymore as his true self.

The big reason why this storytelling worked so well for something so personal and unique is the mesmerizing illustrations. They were extremely detailed and the grainy texture of the lines from being traditionally hand-drawn enhanced the fairy tale aspect and the overall reading experience. The illustrations were also very well balanced as the simple coloring allowed viewers to admire the intricate line art better. The author made the boundaries between the present, the flashbacks, and the fairy tales very clear by having different main colors for each of them, making the reading smooth and simple.

In the end, what makes this book so special lies in the significance of fairy tales. The author Trung Le Nguyen talks about the writing of “The Magic Fish” at the end of the book and says this: “One of the odd challenges of writing a story about characters living within any social margins is the gravity of the marginalization itself. It is such a dense thing, seeming to insist that all the pieces of the story should orbit around it.” Nguyen pointed out that we as people tend to intellectualize complex human experiences, such as immigration, by creating specific words and expressions describing them. These, however, fail to prevent locking those stories and individuals in flat archetypes that ignore the continuing lives—just like fairy tales with their “happily-ever-afters.” By incorporating fairy tales in his book, Nguyen set out to tell a story without specific words or expressions in an attempt to “decenter the gravity of marginalization.”

So, if you wanted me to describe what this book is about, I’ve got no words for it. But what I do know is that this book deserves your attention for the colorful perspective, the delicate art, and the great purpose.